Is it possible to enjoy a movie that has a jerk for a protagonist? After watching P. L. Travers in Saving Mr. Banks I would say the answer is “no”. Then I remembered another film, As Good As It Gets, which has one of the rudest, most abrasive protagonists in storytelling, a film I’ve watched with pleasure many times.

Apparently, my answer should be a qualified “yes”. Let’s see what makes one movie a classic and the other forgettable.

In my service to all of you and this blog I watched Banks again. I wanted to check its Enneagram (which is all in order) and re-examine Emma Thompson‘s performance as Travers. If Jack Nicholson‘s Melvin Udall is a more compelling character than Travers, it will not be Thompson’s fault. I think she’s first tier. Where Travers falls apart will be the fault of the writer and director (and, perhaps, the real life Travers, who was no peach). I started the second viewing with a little bit of anticipation that, unfortunately, quickly devolved to skimming in disgust. Why would anyone watch this thing?

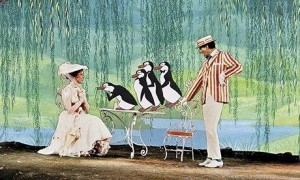

The obvious answer is “Walt Disney”. He is complex and his creativity is engaging. The making of Mary Poppins, which is the best part of Banks, is fun. Would this movie have been more watchable if the writer had stuck to the Hollywood scenes and tossed out the Australia childhood flashbacks? Certainly they were the first and most consistent part of the film that I skipped through. No disrespect to the Scruffy Irish Lad but his scenes were depressing and stopped the film cold. The insinuation (during the Poppins premiere scene) that George Banks’ misplaced priorities in any way compared to the abuse Travers’ father dished out is ludicrous and insulting. The fictional Banks provides for his family, offers them a stable home and struggles with middle-aged problems. Travers Goff is a drunk who impoverishes his family and, through neglect, damages his health and ultimately dies. Comparing real fathers to fictional ones is a lovely device, but this equivocation is appalling. I think that I’m supposed to feel sympathy for Travers in this scene, but I don’t. She mourns her loss and is grateful that her real father, through the medium of storytelling, is redeemed via Mr. Banks, but she shows no sign of changing her own character for the better.

Melvin Udall, on the other hand, is a character who changes dramatically. He’s likable by the end, while still retaining his difficult nature.

Although Udall and Travers introduce themselves in a rude way, only As Good lets the other characters berate the protagonist. Udall may say horrible things, but he’s called on the carpet for it. His character is a wonderful mini-catharsis: he says things aloud that we secretly say to ourselves in our most irritable moments, and then he’s punished for them. The fact that we keep those thoughts to ourselves is rewarded and encouraged by the little morality play enacted in As Good.

No one berates Travers. She is in an economic position of power (she still retains the copyright), so no one has the authority to challenge her. Even Walt is tactful. Someone this ill-mannered really deserves a comeuppance and she gets none. If the Australia scenes are supposed to drum up our sympathy in lieu of Travers getting a proper dressing down, I say they failed.

Udall and Travers are both humanized by a character that opens up their hearts. Travers has her driver, Ralph (the fabulous Paul Giamatti), to whom she finally grants the permission of her first name. Udall gets the dog, Verdell. Here’s a pro-tip: if you want to make your character as sympathetic as possible, let him be won over by an adorable dog. Really, it’s almost like cheating. A driver with a handicapped daughter, which is what Ralph ends up to be, is strictly amateur hour in the pull-the-heartstrings Hollywood chump show. I feel less manipulated by the dog scheme, actually.

Udall has another possible advantage in the “who’s more likable” category. He’s a man. I know; I hate to say it, but I have to bring it up. When Nicholson raises the corners of his eyebrows and sneers, I just giggle. When Thompson frowns and presses her lips together, I cringe. Maybe, it’s simply that we don’t want to see a mean woman as a protagonist. I will not discount this aspect of the problem.

Ultimately, though, Travers is never redeemed, and that is the main difference between the two. It’s funny; Banks works so hard to redeem the fathers of the movie that it forgets its most important character who needs redemption. Mary Poppins herself, at least in the Disney movie, is never redeemed. She blows in and out with the wind, helps her family, and never changes herself. (I’m not a big Poppins fan, either.) What is it with Travers’ world and the refusal to hold women accountable for being steadfastly unpleasant?

Good old Aristotle probably summed this all up. I’m pretty sure that one of the categories I covered when I reviewed him was the bad-man protagonist who was all flaw and no uplift. Again, the moral to storytellers is always: Don’t ever think you’re smarter than Aristotle.

A hateful protagonist who offers nothing more than a shocking rudeness will always fail. You heard it here first.